Two new fossil species of Bruchomyiinae (Diptera: Psychodidae), namely: Nemopalpus velteni Wagner, sp. n. (Burmese amber) and N. inexpectatus Wagner, sp. n. (Baltic amber), are described and figured, together with four extant species from the Neotropical Region: N. stuckenbergi Wagner, sp. n. (Chile), N. amazonensis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n., N. similis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n. (both Brazil) and N. cancer Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n. (Colombia). The terminalia of N. pilipes Tonnoir, 1922 are illustrated for the first time. Based on the shape of the male terminalia, N. stuckenbergi sp. n. is probably closely related to N. rondanica Quate & Alexander and to N. stenhygros Quate & Alexander, both of which occur in Brazil. Nemopalpus similis sp. n. (Brazil), N. pilipes Tonnoir (Paraguay), N. dampfianus Alexander (Mesoamerica) and N. capixaba Biral Dos Santos, Falqueto & Alexander (Brazil) form a distinct species-group of their own. Nemopalpus amazonensis sp. n. (Brazil) and N. rondanica Quate & Alexander (Brazil) are closely related, as are N. cancer sp. n. and N. phoenimimos Quate & Alexander, both from Colombia. The presence or absence of tergal extensions and ornamental setulae on various segments are here regarded as unreliable characters to assess relationships among Neotropical Nemopalpus. The internal male and female terminalia of Bruchomyiinae provide more-useful apomorphic features and it is here postulated that the Phlebotominae are probably phylogenetically older than Bruchomyiinae.

INTRODUCTION

The Diptera family Psychodidae has a worldwide distribution and comprises six subfamilies: Bruchomyiinae, Phlebotominae, Psychodinae, Sycoracinae, Trichomyiinae and Horaiellinae. The fascinating Bruchomyiinae are composed of three genera: Nemopalpus Macquart, 1838, Bruchomyia Alexander, 1920 and Eutonnoiria Alexander, 1940 (Duckhouse 1973; Young 1979) and is considered to be the most plesiomorphic subfamily of the Psychodidae by some authors (e.g., Quate & Alexander 2000). Adult Bruchomyiinae are superficially similar to phlebotomine “sand-flies” (Phlebotominae) and frequently occur together with these morbiferous insects in the field. Mouthparts of female Bruchomyiinae are not adapted for blood-feeding as in Phlebotominae, however. Larvae of only two species are known (Satchell 1953; Mahmood & Alexander 1992), and aside from the habitat preferences of some species, the ecology of the subfamily remains entirely unknown.

General features of the Bruchomyiinae are: body culiciform, eyes circular, no eyebridge, mouthparts of female non-functional, antennae elongate with very small ascoids, thorax without allurement organs, legs and wings elongate, with long CuA1, CuA2 and A. Abdomen of male with allurement organs in some New World, Australian and New Zealand species; inversion of the terminalia involving segments 7 and 8; cerci usually unmodified; internal terminalia with two testes, two sperm ducts, a sperm pump, and a single genital orifice. Female with a single, considerably enlarged spermatheca. sperm duct, and genital orifice. The underlined apomorphic features distinguish Bruchomyiinae from Phlebotominae and all other Psychodidae (s.l.).

Some fossils from Baltic and Dominican amber are assigned to the Bruchomyiinae (Edwards 1921; Schlüter 1978; Wagner 2006). Based on the general morphology of the terminalia, the Dominican amber species can be easily related to the extant fauna of Mesoamerica, but the Baltic amber species belong to extinct evolutionary branches. Most likely climatic changes since the end of the Tertiary have caused the extinction of Bruchomyiinae in Europe and probably in non-tropical Asia.

The occurrence of Bruchomyiinae appears to be strongly determined by the presence of primary forests. The ancient forests of Africa and South Asia, in particular, remain largely undersampled and undescribed taxa should be expected. Given the rate of global deforestation, however, it is unlikely that all undescribed species will be discovered before indigenous habitats are destroyed. Most species (23 species in two genera) are currently known from primary forests in the Neotropical Region. The known fauna of the Afrotropical Region comprises six species in two genera; three species (two of which are only known from females) occur in the Oriental Region; and two species are known from the Australasian Region (Duckhouse 1978; Duckhouse & Lewis 1980).

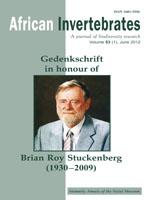

The late Brian Stuckenberg promulgated the hypothesis that Nemopalpus represents a Southern Hemisphere genus that exhibits a Gondwanan distribution pattern (e.g., Stuckenberg 1962). He was thus interested in amber fossils and two additional species from Burmese and Baltic amber are described herein. The collection of extant Bruchomyiinae he largely compiled at the KwaZulu-Natal Museum, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (NMSA) contains several Neotropical species that he collected, or that were donated by colleagues. These new taxa are described below. Figures of the male terminalia of the Neotropical species N. pilipes Tonnoir, 1922, are provided for comparative purposes.

Figs 1–4.

New fossil species of Nemopalpus: (1–3) N. velteni Wagner, sp. n., male: (1) habitus in amber; (2) head with mouthparts and basal antennomeres; (3) terminalia, dorsal view; (4) N. inexpectatus Wagner, sp. n., male terminalia, lateral view. Sources of figures: Figs 1–3 (RW); Fig. 4 (BS with additions by RW). Scale bars: Fig. 1 = 0.5 mm; Figs 2, 3 = 0.1 mm; Fig. 4 = scale unknown.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The majority of specimens used in this study were prepared by the late Brian Stuckenberg. They were cleared, dissected and some stained. Dissected parts, comprising the head, wing, legs, abdomen and terminalia, are embedded in Canada balsam under a cover slip. In some cases, body parts of individual specimens are divided on to more than one slide and some parts are missing. Brian Stuckenberg further prepared a number of excellent figures of the undescribed species which have been used herein.

Although Bruchomyiinae are known to possess five palpomeres, the basal segment could often not be identified on the preserved specimens, and in such cases, only the proportions of palpomeres 2–5 could be provided. The morphological terminology used in this paper follows Cumming and Wood (2009). Concerning nomenclature, we follow the proposal of Sabrosky (1999: 211), who justified in a long note the adoption of the name Nemopalpus over Nemapalpus.

TAXONOMY

Genus Nemopalpus Macquart, 1838

Nemopalpus: Macquart 1838a: 219; 18386: 223; Sabrosky et al. 1999: 211. Type species: Nemopalpus

flavus Macquart 1838, by monotypy. Nemapalpus Macquart, 1838a: 81, 211, pl. 12; 18386: 85, 215, pl. 12; Sabrosky et al. 1999: 211. Rejected original spelling.

Nemopalpus velteni Wagner, sp. n.

Figs 1–3

Etymology: The specific name is dedicated to Jürgen Velten (Idstein, Germany), who kindly provided the inclusion for study.

Description:

Male.

Measurements: Overall length 2.1 mm. Wing length 2.2 mm.

Head (Fig. 2): Typical of the genus, with circular eyes, no eye bridge. Mouthparts of male non-functional. Relative lengths of four clearly visible palpomeres: 20-15-25-25; overall length of palpus ∼0.56 mm. Antenna with spherical scape and pedicel, and 14 elongate tubular flagellomeres clothed in long setae. Due to dense vestiture the presence of ascoids on flagellomeres could not be detected. Relative lengths of antennomeres: 8-8-26-21-22-22-20-17-16-16-15-14-12-10-10-10; antennal length 1.65–1.70 mm. Measurements of palpus and antennal segments are approximate as articles are not arranged in a single plane.

Thorax. Haltere and legs lacking specific features. Wings difficult to reconstruct due to high degree of translucency, partly folded, with one wing tip missing. Wing ca 2.5× longer than wide; Sc ending free in wing area at ca 0.25 wing length; R1 elongate; fork R2+3/R4+5 positioned basally; forks R2+R3 and R4+R5 at ca basal third of wing; tip positioned between R4 and R5; fork M1+2 (most distal of forks) positioned at ca middle of wing; M3 arising basally from M1+2 stem; short cross-vein positioned between M1+2 and M3 at short distance distally from that fork; CuA1 arising near point where cross-vein joins M3; CuA2 moderately short, not reaching posterior wing margin; anal vein indistinguishable.

Abdomen: With 8 pregenital segments, plus terminalia (Figs 1, 3). Terminalia inverted, segmentation forming torsion unclear. Terminalia relatively simple, gonocoxite pipe-shaped, virtually straight, shorter than slightly bent gonostylus. Tergum 9 sub-rectangular, with fleshy, setose cerci; tergum 10 conical. Aedeagus elongate thin, tube-shaped.

Holotype: ♂ MYANMAR: Burmese amber; Cretaceous, Albian (private collection of J. Velten, Idstein, Germany).

Notes: Nemopalpus velteni sp. n. represents the oldest known fossil Bruchomyiinae and is distinguished by its overall smaller size and in the shape of the terminalia. The structure of the terminalia is much simpler than the geologically younger Baltic amber species N. inexpectatus sp. n., described below. The specimen record greatly increases the known distribution of fossil Bruchomyiinae.

Nemopalpus inexpectatus Wagner, sp. n.

Fig. 4

Etymology: The specific epithet reflects the unexpected discovery of an additional Nemopalpus species from Baltic amber.

Description:

Male.

Head & thorax: Typical of the genus.

Abdomen: Terminalia with large gonocoxite in lateral view, increasing in width distally. Gonostylus small, elongate, blade-like, S-shaped, with fringe of setae, between which lies well sclerotised tip of aedeagus. Tergum 9 cone-shaped, cerci small, just aside cerci with a pair of small trifid appendages along ventral margin of tergite (function unknown).

Holotype: ♂ (Z 3900) Baltic Amber; Late Eocene (Amber collection of the Geowissenschaftliches Zentrum der Universität Göttingen).

Notes: This specimen was repeatedly examined (e.g., Hennig 1972; B.R. Stuckenberg pers. comm., 2002), but never recognised as a separate species. After the recovery and redescription of other Nemopalpus (Wagner 2006), this species is now easily distinguished from other Baltic amber taxa. Although only visible in lateral view, the terminalia are unique. Gonocoxites of N. hoffeinsi Wagner, 2006 and N. tertiariae Meunier, 1905 are elongate, tube-shaped; those of N. molophilinus Edwards, 1921 are similar in shape, but the gonostylus is bipartite and larger than the gonocoxite. In addition, the new species has a pair of remarkable trifid appendages on tergum 9, indicated by an arrow in Fig. 4.

Nemopalpus stuckenbergi Wagner, sp. n.

Figs 5–10

Etymology: The species name is dedicated to the late Brian Roy Stuckenberg. Brian visited Chile with the specific aim of collecting Nemopalpus, but was only successful on the last day of his visit.

Description:

Male.

Head: Eyes oval, separated by ca 4 facet diameters. Scape 2× as long as wide, pedicel spherical, 1.5× as long as scape. Flagellomere segments elongate. Relative lengths of antennomeres: 4-6-40-27-27-24-22-22-21-18-17-15-15-13-11-10. Relative lengths of four visible palpus segments: 17-24-26-55. Area of Newstead scales present on second segment.

Thorax: Slide with wings probably lost and cannot be described.

Abdomen: With 8 pregenital segments plus terminalia. Terga of segments 6 and 7 each with lateral extensions clothed in ornamental setulae (Fig. 5). Segment 8 and terminalia each rotated by ca 90°. Terminalia: Tergum 9 rectangular, with rounded distal margin (Fig. 8). Tergum 10 conical, setose. Cercus oval, slightly longer than wide. Gonocoxite about 2× as long as its greatest width; in ventral and dorsal view appearing slightly bent, clothed in strong setae. Gonostylus as long as gonocoxite, bent with distal “nose”. Aedeagus small, with sharp apex; vasa deferentia short and wide. Aedeagus sclerite thin, laterally depressed. Paramere dorsobasal to gonocoxite, appearing well sclerotized with short, curved tip (Fig. 7).

Female.

Head with large oval eyes; separated by 3–4 facet diameters. Antenna: Scape 2× as long as wide, pedicel spherical, 1.5× as long as scape. Flagellar segments elongate; relative lengths of antennal segments: 4-6-32-19-19-19-16-16-16-14-14-13-11, distal segment lost. Flagellomere 1 with two pairs of ascoids, remainder with only single pair each in distal third. Paired ascoids slightly offset. Antenna of the female from the University Park complete, its distalmost flagellomere is approximately same length as penultimate with a short tip and pair of ascoids. Palpus with four visible segments; relative lengths: 17-27-20-82 [specimen from University Park differs in relative lengths of visible palpus segments: 18-25-20-55].

Thorax: Elongate legs lacking specific features. Wing length: 4.9 mm. Radial and medial forks at about same level.

Abdomen: Composed of seven pregenital segments of usual size and shape, tergum and sternum 8 conjoined to a thin sclerotised ring (Fig. 9). Cavity of 9th segment with two oval clusters of expanded setae (Fig. 9). Spermatheca very large, consisting of two successive parts of unequal size (Fig. 10); cercus small.

Holotype: ♂ ‘Chile: Valdivia, park adjacent to university, forest residual, 3.VII.1987, leg. B.R. Stuckenberg’ (NMSA). On single slide mount; wings missing.

Paratypes: 1♀ same data as holotype, 1 slide with legs and wing, 1 slide with head, thorax and wing; 1♀ ‘Chile: Valdivia, Isla Teja, swampy woodland near university farm, 13 Dec[ember] 1984, leg. J.A. Downes [1667/I/46]’ (both NMSA).

Notes: The male terminalia are in general similar to N. rondanica Quate & Alexander, 2000 (Brazil, Rondônia) and N. stenhygros Quate & Alexander, 2000 (Brazil, Pará) (Quate & Alexander 2000), but both those species lack extended abdominal tergites and ornamental setulae. The presence of clusters of setae in the female genital cavity is also not unique to the new species, similar structures having been mentioned in N. dampfianus Alexander, 1940 by Fairchild (1952), and Brian Stuckenberg (pers. comm., 2004) noted ‘unmodified setulae’ in the same area in females of N. australiensis Alexander, 1928.

Figs 5–8.

Nemopalpus stuckenbergi Wagner, sp. n., male: (5) abdomen, segments 4–8 and terminalia, lateral view (note tufts of ornamental setulae on lateral extensions of tergites 6 and 7, and torsion of segment 8 and terminalia); (6) cleared terminal pregenital segments and terminalia, lateral view (ornamental setulae on lateral extensions of terga 6 and 7 removed); (7) abdominal segments 6 to 8 and terminalia, ventral view (ornamental setulae on terga 6 and 7 removed); (8) terga 9–10 and cerci, dorsal view. (All figures by BS). Scale bars = 0.5 mm.

Figs 9, 10.

Nemopalpus stuckenbergi Wagner, sp. n., ♀ paratype from Isla Teja: (9) abdomen, segments 7–8 and terminalia, latero-ventral view; (10) spermatheca (same scale as fig. 9). (All figures by BS). Scale bar = 0.2 mm.

Nemopalpus amazonensis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n.

Figs 11–16

Etymology: The specific name, which refers to the type locality, was initially proposed by Brian Stuckenberg, as indicated by annotations on his original figures.

Description:

Male.

Head: Distance between oval eyes approx. 1 facet diameter (Fig. 12). Eyes appear in the shape of mulberries (probably indicative of crepuscular or nocturnal activity). Scape 2× as long as wide, 1.5× as long as spherical pedicel. Flagellomeres elongate, each narrower at about midlength; relative lengths of antennomeres: 6-4-35-28-29-28-29-27-26; distal segments missing. All flagellomeres have (probably) single mushroom-shaped ascoids on the distal swelling (Fig. 13). Relative lengths of the four visible palpus segments: 18-19-18-57; [length of distal striate segment probably underestimated, because they are not positioned horizontally]. No Newstead scales apparent.

Thorax: Wing length 4.0 mm. Venation with radial fork near tip of R1, medial fork in basal half of wing, close to 2nd cell (Fig. 11). Legs lacking specific features.

Abdomen: With 8 pregenital segments and terminalia. Tergum 6 without lateral extensions, but with median cluster of small circular pores (possibly associated with glands). Terminalia inverted, segments 8 and 9 each rotated by 90°. Terminalia: tergum 9 rectangular, distally narrower and rounded. Tergum 10 conical, setose, as long as cercus. Cercus oval, ca 2× as long as wide (Fig. 16). Gonocoxite 2× as long as wide, decreasing in width distally. Gonostylus about same length as gonocoxite, slightly folded at ca midlength; distal part approximately sickle-shaped, flattened. Aedeagus with a laterally compressed basal sclerite, distally with a heavily sclerotised rectangular ‘plate’ and short median tip. Vasa deferentia weakly dilated (Fig. 14).

Holotype: ♂ ‘Brazil: Amazonas, 27 km E[ast of] Manaus, 17 March, [probably 1974], leg. D.G. Young’ (NMSA).

Paratype: ♂ ‘Brazil: Mato Grosso, Rio Aripuana, tree trunk, 16–20 Aug[ust] 1974, leg. D.G. Young’ (NMSA). On two slide mounts.

Notes: Based on the general shape of the terminalia, N. amazonensis sp. n. is related to N. rondanica from the Brazilian State of Rondônia (Quate & Alexander 2000). The gonostyli are similar in shape, but the presence of pores on tergum 6, together with the shape of the aedeagus, distinguish the new species from its congeners.

Figs 11–16.

Nemopalpus amazonensis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n.: (11) wing, (12) head with palpus and basal antennal segments, (13) basal and distal flagellomeres with ascoids; (14) segments 6 to 8 and terminalia ventral view; (15) gonostylus; (16) tergum 9 and cerci. (All figures by BS). Scale bars: Fig. 11 = 1 mm, Figs 12, 13 = 0.5 mm, Figs 14–16 = 0.2 mm.

Nemopalpus pilipes Tonnoir, 1922

Figs 17–20

Nemopalpus pilipes: Tonnoir 1922: 130–136.

Nemopalpus maculipennis Barretto & d'Andretta, 1946: 64–66.

Nemopalpus vexans Alexander, 1940: 798.

Tonnoir's (1922) description is sufficient to distinguish the species, but he did not provide figures or description of the terminalia; this is provided below, together with a brief redescription.

Redescription:

Male.

Head: As in other species. Palpus lacking Newstead scales. Antenna with scape, pedicel and 14 flagellomeres; ascoids unrecognisable. Relative lengths of antennomeres: 14-11-63-43-43-43-43-42-42-42-42-37-34-30-28-23.

Thorax: Wing length ca 4.5 mm. Discal cell extremely elongate, origin of vein M2 before end of discal cell. Stem of R2+3 ca 2× as long as R2 and R3.

Abdomen: Lacking lateral extensions of tergites or ornamental setulae. Terminalia: Gonocoxite robust, with inner distal prolongation ending shortly behind distal margin of gonocoxite, with ca 6 strong setae on inner margin; fusion of gonocoxites as a “complex” not evident. Gonostylus ca length of gonocoxite, distally bipartite, dorsal tip stronger than ventral, both clothed in numerous setae. (Aedeagus and its sheath (parameres) have been dissected, so that the original position is difficult to determine.) Tergum 9 ca length of gonocoxite; cercus elongate, ca 0.5× length of tergum.

Holotype: ♂ ‘Nemopalpus [sic] pilipes n. sp. det. A. Tonnoir 1921’ [typed white], ‘Type’ [white label with black margin], ‘Fiebrig, Paraguay, S. Bernardino’ [white], ‘post,ant.’ [legs]. Dissected: terminalia, wings, head and thorax, legs, palpus, antennae all in Canada balsam on individual microslides on a pin. (NHMW)

Allotype: 1♀ ‘Type’ [red label], ‘Nemopalpus pilipes n. sp.’ [handwritten], ‘det. A. Tonnoir 1921’ [typed white label], ‘Fiebrig, Paraguay, S. Bernardino’ [white label]. Pinned, not dissected (NHMW).

Figs 17–20.

Nemopalpus pilipes Tonnoir, 1922, holotype: (17) palpus; (18) tergum 9 and cercus, (19) gonocoxite and gonostylus; (20) aedeagus with paramere. (All figures by RW). Scale bars = 0.2 mm.

Nemopalpus similis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n.

Figs 21–23

Etymology: From Latin similis (similar), referring to the fact that the male terminalia of this species are morphologically similar to several other species.

Description:

Male.

Head: Typical of the genus. Eyes circular, distance between eyes ca 3 facet diameters. Relative lengths of four visible palpomeres: 16-20-24-60, distal segment striate. Newstead scales absent. Antenna with scape, pedicel and 14 flagellomeres. Relative lengths of antennomeres: 11-10-64-45-44-44-44-43-39-37-35-33-32-28-23-22; apiculus of distal flagellomere ca 0.2× article length. A pair of mushroom-shaped ascoids on each of flagellomeres 2–14, possibly also on flagellomere 1.

Thorax: Wing (Fig. 21): Length 3.8 mm. Radial fork comparatively short; M2 originating from distal part of discoidal cell. Legs elongate, lacking specific features.

Abdomen: With small lateral extensions on tergum 5, clothed in elongate, ornamental setulae. Terminalia: Gonocoxites close to one another medially, with inner distal prolongation ending shortly behind end of gonocoxite. With group of ca 8 elongate setae on inner margin medially and few additional strong setae distally. Gonostylus ca length of gonocoxite, distally bent inward, bipartite, dorsal tip longer than ventral, both covered with several setae. Opening of distal ductus shaped like a (morphologically) ventrally open pipe. Two thin sclerites with insertions of setae are positioned on either side (parameres). Tergum 9 ca length of gonocoxite, basally 2× as wide as distally. Cercus ca 0.25× length of tergum 9.

Holotype: ♂ ‘Brazil: Bahia State, near Gandu, 28 September 1985, leg. D.G. Young’ (NMSA).

Notes: This species is a close relative of N. pilipes Tonnoir, 1922 (Paraguay), N. dampfianus Alexander, 1940 (Mesoamerica) and of N. capixaba Biral Dos Santos, Falqueto & Alexander, 2009 (Brazil, Espirito Santo). The terminalia of all are similar in the shape of the gonocoxite, with an inner appendage, and the typically bent, bipartite gonostylus. All four possess thinly sclerotised sheath-like parameres along both sides of the aedeagus. Tergite extensions with ornamental setulae occur in N. similis (segment 5), and N. capixaba (all segments), but not in N. dampfianus and N. pilipes. The close relationship of these species can be based on the shape of the terminalia and the characteristically-shaped parameres. The presence or absence of tergite extensions and ornamental setulae on various segments are surely no features to assess relationships among Neotropical Nemopalpus species.

Figs 21–23.

Nemopalpus similis Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n.: (21) wing; (22) terminalia ventral view; (23) tergum 9 and cerci. (All figures by BS). Scale bars: Fig. 21 = 1 mm, Figs 22, 23 = 0.2 mm.

Nemopalpus cancer Wagner & Stuckenberg, sp. n.

Figs 24, 25

Etymology: The specific name was initially proposed by Brian Stuckenberg, the gonostyle of the male terminalia being shaped like a crab claw.

Description:

Male.

Head: Distance between circular eyes ca 1.5× facet diameter. Antenna with scape, pedicel and flagellomeres 1–3 (distal segments missing, not on slide, but B. Stuckenberg provided a figure of the two distal-most segments, each with a pair of ascoids). Relative lengths of segments: 12-11-74-53-53-; apiculus of distal flagellomere ca one sixth length of the segment (according to B. Stuckenberg). A pair of mushroom-shaped ascoids, seemingly on each flagellomere. Relative lengths of the visible four palpus segments: 20-24-29-60, distal segment striate. An oval field of Newstead scales on 2nd segment. Thorax: Legs missing. Wing length 4.7 mm. Wing venation as usual, medial fork meets r—m cross-vein at lower distal end of the discal cell. Abdomen: Lacking ornamental setulae; sternum 6 slightly enlarged, 7th segment rotated about 90°, 8th segment a thin sclerotised ring, rotated another 90°. Terminalia in lateral view: aedeagus short, less than half length of gonocoxite. Sperm ducts wide in diameter. Tergum 9 thin, elongate; cercus large. Gonocoxite with basal finger-shaped setose inner appendage. Distal half of gonostylus dished, bipartite; dorsal appendage finger-shaped blunt, ventral tip sharp. Holotype: ♂ ‘Colombia: Valle, Dept [= Dept. of Valle de Cauca], Penas Blancas, light trap, 23 February 1975. leg. J.E. Brown’ (NMSA). Mounted on two slide mounts, one with head, one with wings and abdomen.

Notes: In this new species segments 7 and 8 are probably involved in the torsion of the terminalia. The shape of the terminalia indicates a relationship to N. phoenimimos Quate & Alexander, 2000, which is also known from Colombia. The inner appendage on the gonostylus of N. cancer sp. n. distinguishes these species.

DISCUSSION

Controversy remains regarding the systematic position of the Psychodidae sensu lato within the higher classification of the Diptera. Similarly, the phylogenetic relationships among subfamilies of Psychodidae are cause of a long conflicting debate. However, the Bruchomyiinae is one sufficiently acknowledged subfamily, which at present comprises three genera: Bruchomyia Alexander that is restricted to the Neotropical Region, Eutonnoiria Alexander from the Afrotropical Region, and Nemopalpus Macquart that encompasses the remaining Bruchomyiinae in the Palaearctic, Afrotropical, Australasian and Neotropical regions. The genera seem to represent independent phylogenetic lines. In particular, Nemopalpus species denote a great variability of morphological features. The species described or redescribed above now provide information that will permit a substantial revision of the subfamily, and elucidation of the phylogenetic lineages within the Bruchomyiinae (Stuckenberg & Wagner in prep.).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank B. Muller (NMSA) for providing Brian Stuckenberg's slides together with scans of his original unpublished illustrations of the new species. P. Sehnal (Natarhistorisches Museum, Vienna) kindly arranged the loan of the type material of Nemopalpus pilipes Tonnoir. I further acknowledge the useful comments and amendments by two anonymous referees.